Bubble beliefs: Prices are too high but going higher

Table of contents

What’s a stock market bubble? Back in March, I defined a bubble as “a self-sustaining rise in prices over time resulting in the speculative trading of an obviously overvalued asset,” and I said the U.S. stock market was “not even close” to a bubble. Things have changed in the past eight months, and today we are indeed close to a bubble. A key driver of bubble dynamics has emerged: bubble beliefs.

I’ve previously described the main symptoms of bubbles – the Four Horsemen of the Bubble Apocalypse – which include bubble beliefs:

Second Horseman, Bubble beliefs: Do an unusually large number of market participants say that prices are too high, but likely to rise further?

As of today, the Second Horseman has galloped onto the scene. Many market participants are buying equities even though they believe the market is overpriced. Their intention is to sell at a profit to a greater fool in the future.

Kindleberger (1996) contains many passages that describe bubble beliefs leading to speculative trading. Let me give two of them. First, London, 1720:

The additional rise above the true capital will only be imaginary; one added to one, by any stretch of vulgar arithmetic will never make three and a half, consequently all fictitious value must be a loss to some person or other first or last. The only way to prevent it to oneself must be to sell out betimes, and so let the Devil take the hindmost.

Chancellor (2000), a valuable account of historical bubbles, uses the last four words of the London text as its title.

Second, Chicago, 1890:

In the ruin of all collapsed booms is to be found the work of men who bought property at prices they knew perfectly well were fictitious, but who were willing to pay such prices simply because they knew that some still greater fool could be depended on to take the property off their hands and leave them with a profit.

Bubble beliefs are a little different than the standard idea of “investor sentiment.” Consider the “sentiment” during the above-described bubbles in Chicago and London. Would you describe these investors as bullish? Optimistic? Displaying positive sentiment? Well, they are short-term positive, long-term negative. Similarly, consider a poker player who is holding four aces, but the poker game is being held on the deck of the Titanic. Short-term positive, long-term negative.

Is it irrational to have bubble beliefs? Not necessarily. At any one point in time, it might be perfectly rational to predict that the market will rise next year, and then fall the year after that. But you can’t have bubble beliefs forever; eventually “the year after that” will arrive. The Titanic is going down eventually.

“Prices are too high …”

The main idea of bubble beliefs is that many market participants believe that stock prices are too high but are willing to hold equity anyway. That’s where we are today.

I base this conclusion on the Yale School of Management’s U.S. Stock Market Confidence Indices.[1] As of October 2024, 71.5% of individual investors surveyed said the market was overvalued. That’s the second highest monthly value ever observed, with only April 2000 being higher (at 72.3%).

Yale asks two questions:

- Will the market go up? They report percent respondents saying the Dow Jones Industrial Average will go up over the next year.

- Is the market overvalued? They report percent respondents saying, “Stock prices in the United States, when compared with measures of true fundamental value or sensible investment value, are too high.”

Table 1 shows the averages of these values from April 1999 to October 2024, and the three individual months where the market was deemed most overvalued.

Table 1

|

Percent of respondents saying market … |

||

|

... will go up |

… is overvalued |

|

|

Average, 1999-2024 |

75.3 |

43.9 |

|

Apr-00 |

76.3 |

72.3 |

|

Jun-21 |

70.0 |

71.4 |

|

Oct-24 |

69.2 |

71.5 |

Judging only by overvaluation beliefs, we had a bubble in 2000, a second bubble in 2021, and then a third bubble happening right now.

Some comments on these numbers. First, after 2001, Yale reports trailing 6-month averages. Thus on an apples-to-apples basis, it is conceivable that overvaluation beliefs were actually higher in the calendar month of October 2024 than they were in April 2000.

Second, back in March 2024, I arbitrarily declared that my criteria for the Second Horseman was “I need 65% or more respondents agreeing that” the market was overvalued. Yale’s survey blew past 65% in July, and now we are firmly in bubble territory.

Third, I’ve discussed the Yale survey several times already, and I’ve reviewed related research and evidence on bubble beliefs. We started far from bubble beliefs at the beginning of the year: March 2024 (“not close to bubble territory”) and April 2024 (“no bubble”) but things started to heat up in July 2024 (“getting bubbly”). The Yale survey is red hot now, in terms of belief that the market is overvalued.

“… but going higher”

As you can see from the first column of Table 1, as of October 2024, 69.2% of respondents think the market will go up even though 71.5% of respondents think the market is overvalued. These numbers imply that at least 40.7% of respondents must have bubble beliefs: simultaneously believing that the market will rise and is overvalued.

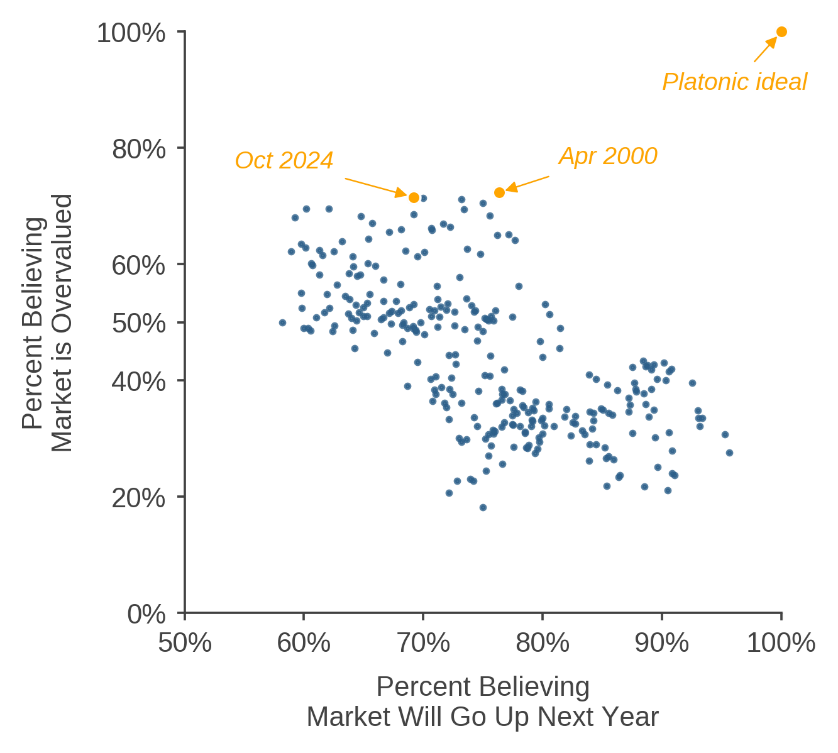

Figure 1 shows question 1 vs. question 2 from April 1999 to October 2024; each point is a monthly observation. The two orange points are April 2000 (on the right) and October 2024 (on the left).

Figure 1: Overpriced but Rising

Let’s talk about the correlation first. The graph shows a downward sloping relation between the two responses over time (the correlation between these two responses is -64%). This correlation reflects a sensible contrarian or mean-reverting set of beliefs. When the market is overpriced, it is less likely to go up next year (upper left corner); when the market is cheap, it is more likely to go up (lower right corner). Of course, the graph does not actually show probabilities; it shows percent of respondents answering “yes” to the two questions. So a more precise description is that when more people think the market is overvalued, fewer people think it will go up.

Next, let’s talk about the average values. U.S. investors are extremely reluctant to say that the market will fall next year; on average, 75.3% say it will rise. Never in the survey’s history has a majority predicted the market will fall. The lowest percentage ever observed was May 2023, when only 58.2% predicted the market would rise. In this sense, when I define a bubble as people saying, “prices are too high but will go higher,” the second part of that phrase is unneeded because people always say prices will go higher. Thus the X-axis only needs to go from 50 to 100. In contrast, investors sometimes say the market is overvalued, and sometimes say it is not overvalued. Thus the Y-axis goes from 0 to 100.

The Platonic ideal of bubble beliefs is the upper right corner of Figure 1 at (100, 100): everyone thinks the market is overvalued but will rise. The closest we’ve ever gotten to that ideal was April 2000 when the tech stock bubble was at its peak.

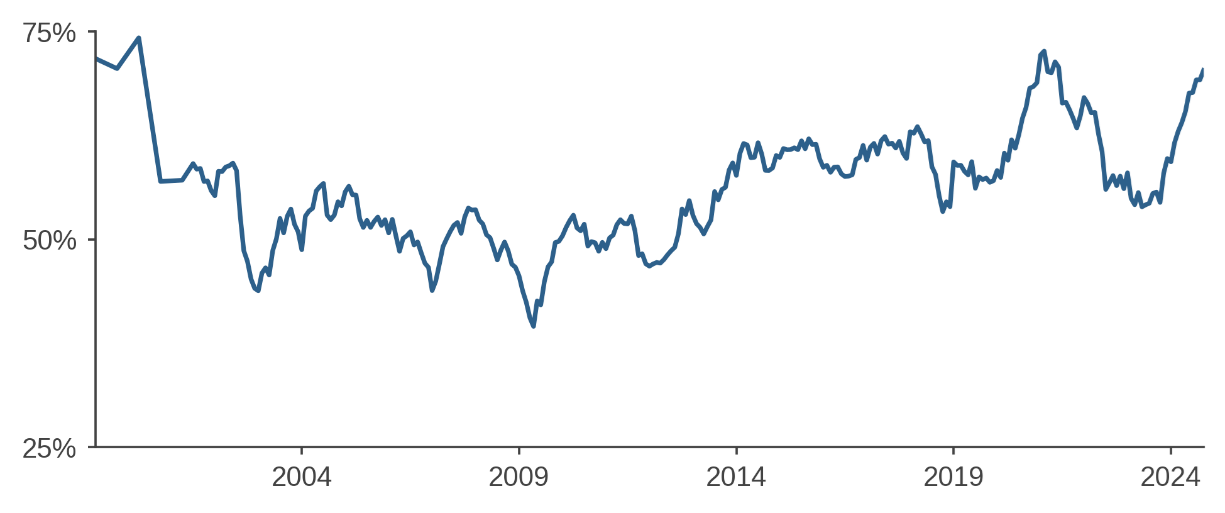

One way to measure bubble beliefs is to calculate the Euclidean distance to this Platonic ideal. Figure 2 shows this distance over time expressed as a fraction where one means you are at the Platonic ideal of (100, 100) and zero means you are the farthest away, at (0, 0).

Figure 2: Proximity to Platonic Ideal of Bubble Beliefs

Figure 2 shows results similar to Table 1: there are three times in history when bubble beliefs have been highest: 2000, 2021, and today. Figure 2 also says the least bubbly market in history was in 2009. Makes sense.

Figure 2 suggests that bubble beliefs today, while not as extreme as 2000, are in the same ballpark as 2021.

Another source of bubble beliefs comes from David Kostin of Goldman Sachs. On October 7, he forecast that the S&P 500 would rise 9.5% over the next 12-months,[2] while on October 18 he forecast average 10-year returns would be only 3%.[3] Short-term positive, long-term negative; that’s bubble beliefs.

Where are we today?

Let me list the three other horsemen:

First Horseman, Overvaluation: Are current prices at unreasonably high levels according to historical norms and expert opinion?

Third Horseman, Issuance: Over the past year, have we seen an unusually high level of equity issuance by existing firms and new firms (IPOs), and unusually low levels of repurchases?

Fourth Horseman, Inflows: Do we see an unusually large number of new participants entering the market?

Here’s where we are today:

First Horseman, Overvaluation: Maybe, yes.

Second Horseman, Bubble beliefs: Absolutely yes.

Third Horseman, Issuance: No, not yet.

Fourth Horseman, Inflows: Not sure. Some anecdotes suggest heightened retail inflows.

So in summary, investor beliefs today are yet another indicator (the previous one was the Saylor-Buffett ratio) saying “bubble, ahoy.”

The bubble is near. But not here yet. Maybe next year.

Endnotes

[1] See https://som.yale.edu/centers/international-center-for-finance/data/stock-market-confidence-indices/united-states.

[2] “Goldman Sachs lifts S&P 500 index target for year-end, next 12 months,” Reuters, October 7, 2024.

[3] “Updating our long-term return forecast for US equities to incorporate the current high level of market concentration,” Goldman Sachs, October 18, 2024.

References

Chancellor, Edward. Devil take the hindmost: A history of financial speculation. Penguin, 2000.

Kindleberger, Charles P. Panics Manias, and Crashes. Wiley, 1996.

Legal Disclaimer

These materials provided herein may contain material, non-public information within the meaning of the United States Federal Securities Laws with respect to Acadian Asset Management LLC, Acadian Asset Management Inc. and/or their respective subsidiaries and affiliated entities. The recipient of these materials agrees that it will not use any confidential information that may be contained herein to execute or recommend transactions in securities. The recipient further acknowledges that it is aware that United States Federal and State securities laws prohibit any person or entity who has material, non-public information about a publicly-traded company from purchasing or selling securities of such company, or from communicating such information to any other person or entity under circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that such person or entity is likely to sell or purchase such securities.

Acadian provides this material as a general overview of the firm, our processes and our investment capabilities. It has been provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe or to purchase, shares, units or other interests in investments that may be referred to herein and must not be construed as investment or financial product advice. Acadian has not considered any reader's financial situation, objective or needs in providing the relevant information.

The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your original investment. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance or returns. Acadian has taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this material is accurate at the time of its distribution, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of such information.

This material contains privileged and confidential information and is intended only for the recipient/s. Any distribution, reproduction or other use of this presentation by recipients is strictly prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient and this presentation has been sent or passed on to you in error, please contact us immediately. Confidentiality and privilege are not lost by this presentation having been sent or passed on to you in error.

Acadian’s quantitative investment process is supported by extensive proprietary computer code. Acadian’s researchers, software developers, and IT teams follow a structured design, development, testing, change control, and review processes during the development of its systems and the implementation within our investment process. These controls and their effectiveness are subject to regular internal reviews, at least annual independent review by our SOC1 auditor. However, despite these extensive controls it is possible that errors may occur in coding and within the investment process, as is the case with any complex software or data-driven model, and no guarantee or warranty can be provided that any quantitative investment model is completely free of errors. Any such errors could have a negative impact on investment results. We have in place control systems and processes which are intended to identify in a timely manner any such errors which would have a material impact on the investment process.

Acadian Asset Management LLC has wholly owned affiliates located in London, Singapore, and Sydney. Pursuant to the terms of service level agreements with each affiliate, employees of Acadian Asset Management LLC may provide certain services on behalf of each affiliate and employees of each affiliate may provide certain administrative services, including marketing and client service, on behalf of Acadian Asset Management LLC.

Acadian Asset Management LLC is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training.

Acadian Asset Management (Singapore) Pte Ltd, (Registration Number: 199902125D) is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 41 114 200 127) is the holder of Australian financial services license number 291872 ("AFSL"). It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Under the terms of its AFSL, Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited is limited to providing the financial services under its license to wholesale clients only. This marketing material is not to be provided to retail clients.

Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority ('the FCA') and is a limited liability company incorporated in England and Wales with company number 05644066. Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited will only make this material available to Professional Clients and Eligible Counterparties as defined by the FCA under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or to Qualified Investors in Switzerland as defined in the Collective Investment Schemes Act, as applicable.

Don't miss the next Acadian Insight

Get our latest thought leadership delivered to your inbox