TSMC: Totally Stupid Market Chaos

Table of contents

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is the world’s largest chip manufacturer; without it, there would be no iPhone and no AI revolution.[1] Its stock price has doubled in the past year. The CEO of Nvidia recently said that when it comes to chipmaking, TSMC was “the world’s best by an incredible margin.”[2]

There’s something else incredible about TSMC: the discrepancy between its stock price in Taiwan and in the U.S. As of October 2024, Taiwan Semiconductor ADRs on the New York Stock Exchange cost 20% more than Taiwan Semiconductor ordinary shares on the Taiwan Stock Exchange. One company, two different prices.

I’ve previously discussed other violations of the Law of One Price (LOOP), but TSMC is a bigger deal because it is a bigger company. While a 20% premium may seem small relative to the 2,000% premium recently observed on a U.S. closed-end fund, that fund was tiny. In contrast, TSMC has a market cap of $1T, making it the world’s 10th largest stock. A 20% mispricing on a $1T stock is kind of a big deal! Indeed, you have to wonder what market cap even means in a world with two different prices.

Now, I don’t have an opinion about whether you should buy shares in the company, but I do have an opinion about LOOP violations: they should not be happening for the world’s 10th largest stock. If you thought that the market was getting more efficient over time, you need to explain why this premium has gone from zero to 20% in the past two years. Let me speak plainly: this mispricing is stupid, chaotic, and embarrassing.

The 20% overpricing of TSMC ADRs is one piece of evidence that the U.S. stock market is approaching bubble territory. Why? Because this specific overpricing has happened before. First, in the U.S. tech stock bubble of 2000, TSMC ADRs had a premium around 80%. Second, in the smaller U.S. stock market bubble peaking in 2021, TSMC ADRs had a premium around 20%. Thus, in these two instances, when the Taiwan market and the U.S. market disagreed about the value of Taiwan Semiconductor, it was the U.S. market that was proven incorrect by subsequent events. I’ve previously discussed evidence that retail investors in Taiwan systematically lose large amounts of money, but when it comes to pricing TSMC, Taiwan beats America.

Why is LOOP being violated for TSMC?

Anytime you see a LOOP violation, you want to ask two questions:

- Why aren’t arbitrageurs enforcing LOOP?

- Who is buying the expensive stock instead of the cheap stock?

Why aren’t arbitrageurs enforcing LOOP?

If assets A and B have identical underlying value but A has a higher price than B, the first question to ask is whether you can mechanically convert B to A. If so, you should buy B, convert it into A, sell it, and pocket the difference. That’s how arbitrageurs enforce LOOP in many situations including ETFs and (usually) ADRs. If A and B are fully fungible, then they can’t be mispriced.

So, when we observe TSMC having a higher price in the U.S. than in Taiwan, that tells us that something must be preventing mechanical arbitrage. The ADR and the underlying are not fully fungible in the short-term. As discussed in Gagnon and Karolyi (2010), the forces impeding ADR arbitrage for TSMC have historically included regulations that prevent the creation of new U.S. shares and limit the ability of U.S. investors to buy in Taiwan. The normal forces of supply and demand cannot operate, and we get a segmented market where prices in the U.S. and Taiwan are out of whack relative to one another.

If mechanical conversion is impossible, then arbitrage involves shorting the ADRs, buying the shares in Taiwan, and waiting hopefully for prices to converge.

Here are the possible issues with this strategy:

- It is impossible to short the ADRs

- It is possible but costly to short the ADRs

- Convergence doesn’t happen quickly. If it costs 1% a year to hold your position, and it takes 21 years for the 20% premium to narrow to zero, you lose money.

- The mispricing worsens, and the 20% premium on U.S. shares widens to an 80% premium. You go bankrupt.

In the specific case of TSMC, shorting in the U.S. is cheap and easy as of today. So issues (1) and (2) do not apply. Rather, it is issues (3) and (4) that deter arbitrageurs from stepping in. Even if you have metaphysical certitude that the premium will go to zero eventually, the arbitrage strategy is a risky bet on the speed of convergence.

Thus the TSMC ADR premium is similar to other long-lasting violations of LOOP including:

- Closed-end funds

- China AH premium

- Dual-class shares such as Royal Dutch vs. Shell prior to 2005 and Google (GOOG vs. GOOGL) today.

As I’ve previously discussed, limits to arbitrage allow LOOP violations to persist. Thus, it is theoretically possible that the premium of 20% will persist for decades.

Who is buying the expensive stock instead of the cheap stock?

Who is overpaying by 20%? Are they stupid? Here are some possible culprits:

- Ignorant investors who are unaware they can buy for less in Taiwan. They are stupidly overpaying.

- Informed investors who are not allowed to buy shares in Taiwan. Such investors would be reluctantly overpaying, not stupidly overpaying.

- Index funds who are forced to specifically buy the ADRs. Here, the stupidity is embodied in the index rules which force the fund to buy overpriced ADRs.

I don’t know who is responsible for the violation of LOOP, but I do know that if you are a long-term investor who is legally able to buy Taiwanese shares, it is a no brainer to buy TSMC in Taiwan and not the U.S.

Let’s do some back-of-the-envelope math. TSMC ADRs are about 20% of TSMC shares outstanding. The total market cap of the ADRs is roughly $230B but the same shares in Taiwan would cost $190B. Thus U.S. investors are overpaying by about $40B. Seems big!

TSMC ADR pricing as a bubble indicator

LOOP violations have been a symptom of market bubbles since 1720. Lamont and Thaler (2002) document many mispricings in the tech stock bubble peaking in 2000, while Makarov and Schoar (2020) show LOOP violations in crypto at times when crypto prices rise rapidly.

The TSMC ADR premium seems to be a valuable market indicator for the U.S. stock market. Here’s The Economist from January 2000:[3]

The world over, there is something weird about the way stock markets value technology companies. Even so, the valuations of some Asian firms listed on the American market seem to defy understanding. The American-traded shares of Taiwan Semiconductor (TSMC) are worth 70% more than they are at home.

Yes indeed, there was “something weird” happening in January 2000: a massive technology bubble in U.S. stocks.

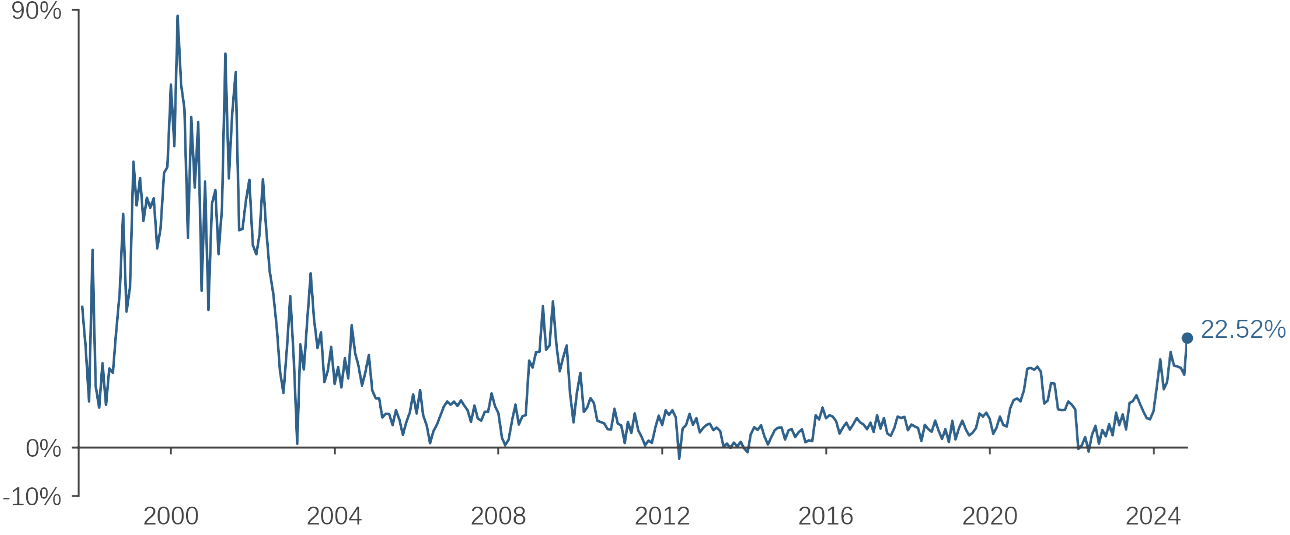

Here’s the TSMC ADR premium over time, using monthly data:

Figure 1: TSMC ADR Premium Versus Local

Through Oct 25, 2024

As you can see, the premium was enormous in 2000, big again in 2009, peaked later in 2021, and is high now. If you view this LOOP violation as an indicator of market craziness, you could say that markets today are at least as crazy as 2021. The Taiwan stock market has liberalized its rules since 2000, and there’s no particular reason to expect that the premium can ever go back to 80%, but I wouldn’t rule it out.

Now, I’m not claiming that the ADR premium is an infallible timing signal for U.S. technology stocks (the 2009 episode warrants further study), but it sure looks consistent with irrational exuberance in the U.S. relative to Taiwan in 2000, 2021, and now.

Multiple violations of the Law of One Price

There’s a rational interpretation of the ADR premium: diversification. Maybe U.S. investors love Taiwanese stocks because they offer uncorrelated return streams. This explanation will not fly for many reasons, but one is that not only is LOOP being violated in the ADR arena, it’s being violated in the opposite way in the closed-end fund arena. Let me explain.

The Taiwan Fund is a closed-end fund that was founded in 1986 and (like the TSMC ADR) trades on the NYSE. It is a diversified fund holding shares trading on the Taiwan Stock Exchange. Can you guess what the largest holding of The Taiwan Fund is? If you guessed TSMC, you’re right: 24% of The Taiwan Fund is invested in TSMC.

Now, given the 20% premium on the TSMC ADR, you might think that The Taiwan Fund would have a big premium. Just based on its holding of TSMC, you’d expect the fund to have a premium of 4.8%. But in fact, The Taiwan Fund currently trades at a discount of 18%. Now, there are many reasons that The Taiwan Fund would trade at a discount (closed-end funds often trade at discounts, partly reflecting their expenses), but one explanation is that AI-crazed American investors are unaware that the world’s most important chipmaker is hidden away in a boring old closed-end fund.

Thus we have multiple violations of the Law of One Price for TSMC. When you put it into an ADR wrapper and sell it in America, it’s worth more than in Taiwan. When you put it into a closed-end fund wrapper and sell it in America, it’s worth less than in Taiwan. One company, three prices.

We saw this exact situation in 2000; hot technology stock ADRs (such as TSMC from Taiwan and Infosys from India) trading at large premiums in the U.S. even while closed-end funds that held these stocks (The Taiwan Fund and The India Fund) languished in obscurity with sizable discounts.

Richard Thaler and I discussed ADR mispricing in the tech stock bubble in Lamont and Thaler (2002). Take that article, change a few words here and there, and the result would be a great description of today’s market. When you find yourself recycling text that you wrote about the tech stock bubble of 2000, you have to wonder if the market is approaching bubble territory.

Endnotes

[1] References to this and other companies should not be interpreted as recommendations to buy or sell specific securities. Acadian and/or the author of this post may hold positions in one or more securities associated with these companies.

[2] “TSMC's Dominance Is Starting to Worry More Than Just Rivals,” Bloomberg, October 21, 2024.

[3] “Over the odds,” The Economist, January 13, 2000.

References

Gagnon, Louis, and G. Andrew Karolyi. "Multi-market trading and arbitrage." Journal of Financial Economics 97, no. 1 (2010): 53-80.

Lamont, Owen A., and Richard H. Thaler. "Anomalies: The law of one price in financial markets." Journal of Economic Perspectives 17, no. 4 (2002): 191-202.

Makarov, Igor, and Antoinette Schoar. "Trading and arbitrage in cryptocurrency markets." Journal of Financial Economics 135, no. 2 (2020): 293-319.

Legal Disclaimer

These materials provided herein may contain material, non-public information within the meaning of the United States Federal Securities Laws with respect to Acadian Asset Management LLC, Acadian Asset Management Inc. and/or their respective subsidiaries and affiliated entities. The recipient of these materials agrees that it will not use any confidential information that may be contained herein to execute or recommend transactions in securities. The recipient further acknowledges that it is aware that United States Federal and State securities laws prohibit any person or entity who has material, non-public information about a publicly-traded company from purchasing or selling securities of such company, or from communicating such information to any other person or entity under circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that such person or entity is likely to sell or purchase such securities.

Acadian provides this material as a general overview of the firm, our processes and our investment capabilities. It has been provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe or to purchase, shares, units or other interests in investments that may be referred to herein and must not be construed as investment or financial product advice. Acadian has not considered any reader's financial situation, objective or needs in providing the relevant information.

The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your original investment. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance or returns. Acadian has taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this material is accurate at the time of its distribution, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of such information.

This material contains privileged and confidential information and is intended only for the recipient/s. Any distribution, reproduction or other use of this presentation by recipients is strictly prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient and this presentation has been sent or passed on to you in error, please contact us immediately. Confidentiality and privilege are not lost by this presentation having been sent or passed on to you in error.

Acadian’s quantitative investment process is supported by extensive proprietary computer code. Acadian’s researchers, software developers, and IT teams follow a structured design, development, testing, change control, and review processes during the development of its systems and the implementation within our investment process. These controls and their effectiveness are subject to regular internal reviews, at least annual independent review by our SOC1 auditor. However, despite these extensive controls it is possible that errors may occur in coding and within the investment process, as is the case with any complex software or data-driven model, and no guarantee or warranty can be provided that any quantitative investment model is completely free of errors. Any such errors could have a negative impact on investment results. We have in place control systems and processes which are intended to identify in a timely manner any such errors which would have a material impact on the investment process.

Acadian Asset Management LLC has wholly owned affiliates located in London, Singapore, and Sydney. Pursuant to the terms of service level agreements with each affiliate, employees of Acadian Asset Management LLC may provide certain services on behalf of each affiliate and employees of each affiliate may provide certain administrative services, including marketing and client service, on behalf of Acadian Asset Management LLC.

Acadian Asset Management LLC is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training.

Acadian Asset Management (Singapore) Pte Ltd, (Registration Number: 199902125D) is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 41 114 200 127) is the holder of Australian financial services license number 291872 ("AFSL"). It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Under the terms of its AFSL, Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited is limited to providing the financial services under its license to wholesale clients only. This marketing material is not to be provided to retail clients.

Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority ('the FCA') and is a limited liability company incorporated in England and Wales with company number 05644066. Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited will only make this material available to Professional Clients and Eligible Counterparties as defined by the FCA under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or to Qualified Investors in Switzerland as defined in the Collective Investment Schemes Act, as applicable.