Conviction, Concentration, and Quant

Advocates of portfolio concentration have claimed that holding a large number of stocks reflects lack of investment conviction, i.e., dilution of a manager’s best ideas. While this assertion may have validity in the context of an investment process rooted in traditional fundamental analysis, the reasoning behind it doesn’t apply to quantitative investing.

Table of contents

In the context of quantitative approaches, the number of holdings is not an appropriate measure of conviction for several reasons: 1) The quantitative process scales easily with the size of the investment universe and the number of stocks owned, so concerns about breadth of holdings extrapolated from limitations of qualitative approaches don’t apply. 2) Quantitative managers seek exposure to investment signals that are most purely expressed through combinations of stocks rather than individual companies, so the number of holdings isn’t a meaningful measure of quant conviction. 3) The quantitative process best accomplishes its objectives through flexibility over holdings, and artificially limiting portfolio size almost inevitably reduces alpha, increases risk, or raises implementation costs.

Concentrated portfolios tend to have high active risk, or tracking error, a trait that may appeal to investors tasked with ambitious performance targets. For investors who do pursue concentrated strategies, quantitative approaches to performance and risk analysis can help to determine whether a candidate manager is deriving returns consistently with a stated investment philosophy. They may also help in identifying unintended exposures when combining multiple concentrated strategies into a portfolio.

Scalability: Qualitative Versus Quantitative Approaches

Proponents of concentration contend that managers have a limited number of good ideas and assert that large portfolios, therefore, reflect dilution of conviction. For qualitative managers who rely on traditional fundamental analysis, this may be a well-founded concern. Such investment processes are inherently difficult to scale. Evaluation and ongoing monitoring of hundreds or thousands of companies and positions requires a large team of analysts, a business model that would stretch the resources of many investment management firms and raise risk of inconsistency in approach and judgment. In such a context, deterioration of forecast conviction likely accompanies breadth, so concentration seems prudent.

This notion is related to Grinold and Kahn’s “Fundamental Law of Active Management,” IR ≈ skill * square root of breadth, where skill reflects the correlation between forecasts and actual outcomes, and breadth reflects the number of independent fore-casts made.1 The Fundamental Law suggests that a discretionary manager with specialist experience in a narrow market sector indeed may be better off concentrating on that small investment universe if broadening out would entail substantial reduction of predictive ability. But if increasing breadth doesn’t sacrifice skill, taking advantage of the available opportunities benefits by diversifying away un-compensated risk and improving the signal-to-noise ratio.

The quantitative investment process is expressly designed to scale easily as the investment universe and portfolio expand, implying that concerns about concentration rooted in natural rigidities of qualitative investment approaches don’t apply.2 Evaluating additional stocks in a computational forecasting framework takes little incremental effort, and we would expect to have the same confidence in the forecast for the nth stock as for the first. In a quantitative context, forecast conviction reflects a manager’s confidence that selected attributes help forecast potential future returns.3 In pursuing breadth, challenges in preserving forecast predictive ability include maintaining data quality and monitoring signal efficacy across markets or segments. To preserve forecast conviction, quantitative managers may modulate signal weightings by region, industry, and other variables.4

Assessing Conviction in A Quantitative Context

Quantitative managers identify stock characteristics that they believe predict future returns. Well-known signals include fundamental and technical indicators associated with value, quality, growth, and momentum. Any particular stock exhibits a unique combination of such characteristics, perhaps attractive relative to peers in some respects but not in others. A core challenge of quantitative investing, therefore, is to craft a portfolio from across the investible universe that expresses desirable attributes as intensely as possible while reducing exposure to uncompensated risks.

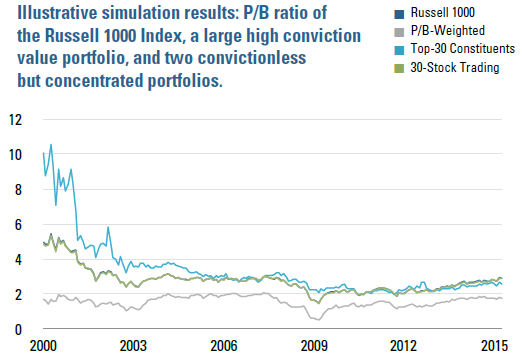

In a quantitative context, therefore, evaluation of conviction should capture both the extent and precision of the portfolio’s exposure to desired characteristics. The number of stocks held isn’t a particularly helpful metric in either regard. As an illustrative example, consider a simulated value strategy benchmarked to the Russell 1000. We can construct a broad hypothetical portfolio with strong value characteristics by reweighting according to P/B. Despite holding an average of more than 950 stocks, this hypothetical portfolio consistently maintains strong value exposure, with an average P/B of 1.6 vs. the benchmark’s 2.8. (Figure 1) Inversely, we can create concentrated portfolios that are convictionless. In the context of this simple value example, holding the benchmark’s top-30 stocks would have resulted in a P/B ratio similar to that of the full index over the past decade. What’s more, we can create a 30-stock hypothetical tracking portfolio whose P/B is visually indistinguishable from the benchmark’s in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Benefits Of Holdings Flexibility in Quant Portfolio Construction

While we have demonstrated that we can create large portfolios with intense exposure to quantitative signals, a high conviction outcome should also precisely express the intended view and preserve the value of signal forecasts through implementation. With this in mind, a disciplined portfolio construction process balances desired exposures against uncompensated risks and trading costs. Holding a large number of stocks provides valuable flexibility in doing so, and we would expect artificially inducing concentration to likely harm performance.

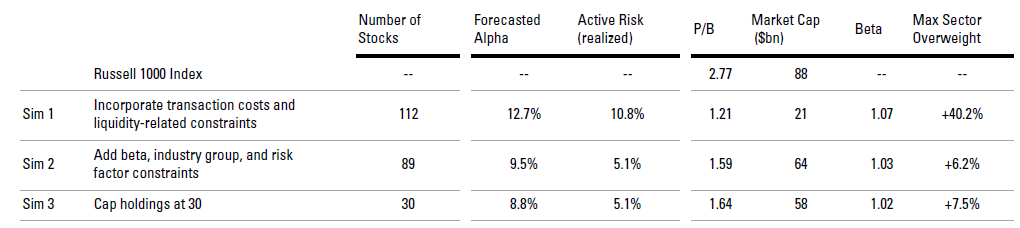

To demonstrate, Figure 2 presents results from three simulations that extend our value theme from the prior examples. Specifically, on every rebalance date we forecast each stock’s return based on its industry-peer-group-relative P/B ratio.5 If driving down price-to-book were our sole objective, we would hold the single stock with the lowest P/B (or a few in the event of a tie)—concentration in the extreme.

Figure 2

In Simulation 1, which incorporates transaction costs and liquidity-based constraints, we hold an average of 112 stocks. The portfolio construction process disperses consumption of liquidity across a large number of holdings in part to limit trading costs, which we assume rise proportionately with shares traded as a fraction of ADV. Portfolio P/B is quite low relative to the benchmark, 1.21 vs. 2.77, indicating an intense value orientation. But the portfolio exhibits material inadvertent exposures, with beta, market capitalization, and sector composition substantially differing from the benchmark. In other words, we haven’t expressed the value view with precision.

In Simulation 2, therefore, we add risk controls, in the form of exposure bounds on beta, industry groups, and a variety of risk factors (e.g., size, leverage, etc.). The highlighted exposures in the table, market cap, beta, and sector composition, snap much closer into line with the benchmark. This increase in precision is paid for with lower forecasted alpha associated with weakened value character (higher P/B). Active risk falls even more, however, by over half, even though we haven’t explicitly controlled for it. (We include no tracking error constraint.)

In Simulation 3 we demonstrate potential costs of concentration in the quant context by capping portfolio size at 30 stocks. Forecasted alpha falls 70 bps (P/B rises), and we see larger size and sector exposure discrepancies versus the index. While these results are specific to this particular scenario, in a quantitative context we generally would expect limiting portfolio size to have costs.6 The number of stocks that make it into the portfolio is a byproduct of a deliberate, disciplined portfolio construction process in which each holding contributes to expected value. We believe arbitrary restrictions on that process are likely to produce inferior outcomes.

Investing In Concentrated Strategies: What to Watch Out For

Concentrated strategies, by their nature, tend to have high tracking error. Although the impact of limiting holdings depends on the nature of the active positions and correlations among the underlying stocks, we generally expect stock-specific risk and active risk factor exposures to increase as portfolios shrink, limiting flexibility to diversify.

High active risk strategies may appeal to investors who face ambitious performance targets. Unfortunately, such strategies, by definition, face a significant hurdle when it comes to maintaining—let alone improving—risk adjusted performance. In order to sustain a target IR, excess return must increase proportionately with active risk. If it doesn’t, then the combination of higher active risk and lower IR suggests higher risk of material underperformance. The Fundamental Law of Active Management highlights the need to increase skill in order to compensate for loss of breadth. This trade-off suggests that investors interested in concentrated strategies should seek out managers with expertise in specialized investment approaches.

Unfortunately, it is easier to identify concentrated managers that generate high tracking error and tell compelling stories than it is to find evidence of requisite skill to offset lack of breadth. Investors considering concentrated strategies may find quantitative performance attribution and risk analysis methods helpful in evaluating whether a manager’s performance is consistent with purported competence and in assessing discipline of portfolio construction.

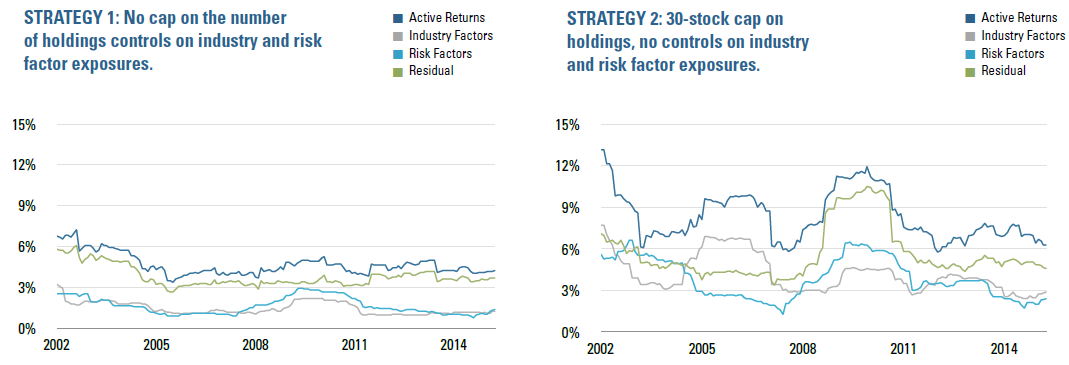

As an example, in Figure 3 we compare risk attributions for two simulated strategies: Strategy 1—the hypothetical portfolio referenced in Sim 1 above, which controls for beta, industry, and risk factor exposures but has no restriction on portfolio size, and Strategy 2—a simulation that includes no limits on industry or risk factor exposures but caps holdings at 30 stocks. Not surprisingly, Strategy 2 has significantly higher active risk, the blue line in each chart. Industry and risk factor exposures (grey and light blue) account for much greater variation in Strategy 2’s active returns than in Strategy 1’s, at times exceeding variability of residual returns (green). In other words, common exposures allowed to creep in through gaps in portfolio construction have become material drivers of active risk relative to stock selection. If Strategy 2 were marketed on the basis of a manager’s stock picking ability, then this analysis would raise a caution flag.

Figure 3

Combining multiple concentrated strategies into a coherent portfolio also presents non-trivial challenges. Risk factor exposures may be non-transparent and unstable owing to idiosyncrasies in specialized managers’ investment processes and unsystematic portfolio construction. We would also expect to find commonalities in the behavior of apparently distinct discretionary managers, reflecting the very psychological biases that quant managers seek to exploit. As such, a portfolio composed of seemingly disparate concentrated strategies may leave behind unintended loadings on factors such as momentum or size.

Conclusion

Active quantitative mangers may generate value through a variety of proprietary means, for example unique data, signals, or timing approaches, as well as superior portfolio construction, risk management, or implementation. We believe hard-won advantages in any of these areas may enable a quantitative manager to consistently add value. While such strategies are highly attractive, they may be difficult to distinguish on the basis of heuristics, such as the number of holdings. What’s more, conclusions about a quant manager’s conviction drawn from metrics relevant to qualitative investment processes may mislead and distract from more meaningful analysis.

Endnotes

- For assumptions, derivations, examples, and extensions of the Fundamental Law see: Grinold, Richard and Ronald Kahn, Active Portfolio Management, Second Edition, (McGraw Hill, 2000) and Clarke, de Sliva, Thorley, “The Fundamental Law of Active Portfolio Management”, Journal of Investment Management, 2006, pp. 54-72.

- Academic literature around the “best ideas” topic includes Cohen, Polk, Silli, Best Ideas, Working Paper, 2009 and Baks, Busse, Green, Fund Managers Who Take Big Bets: Skilled or Overconfident, Working Paper, 2006. Such research does not tend to distinguish between qualitative and quantitative investment approaches.

- Forecasts are typically based on proprietary models. There can be no assurance forecasts will be achieved.

- To prevent overfitting from engendering unfounded confidence, quantitative managers should monitor complexity of their forecasting frameworks.

- This signal is distinct from any that Acadian uses in live strategies. We do not believe that it has predictive value, and the purpose of the simulations is not to test it. We therefore do not display average returns in the above simulation results.

- In unreported simulations, we consider consequences of capping holdings without controls on industry and risk index exposures. In this case too, forecasted alpha decreases and realized active risk increases.

Hypothetical

Acadian is providing hypothetical performance information for your review as we believe you have access to resources to independently analyze this information and have the financial expertise to understand the risks and limitations of the presentation of hypothetical performance. Please immediately advise if that is not the case.

Hypothetical performance results have many inherent limitations, some of which are described below. No representation is being made that any account will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those shown. In fact, there are frequently sharp differences between hypothetical performance results and the actual performance results subsequently achieved by any particular trading program.

One of the limitations of hypothetical performance results is that they are generally prepared with the benefit of hindsight. In addition, hypothetical trading does not involve financial risk, and no hypothetical trading record can completely account for the impact of financial risk in actual trading. For example, the ability to withstand losses or to adhere to a particular trading program in spite of trading losses are material points which can also adversely affect actual trading results. There are numerous other factors related to the markets in general or to the implementation of any specific trading program which cannot be fully accounted for in the preparation of hypothetical performance results and all of which can adversely affect actual trading results.

Don't miss the next Acadian Insight

Get our latest thought leadership delivered to your inbox

Legal Disclaimer

These materials provided herein may contain material, non-public information within the meaning of the United States Federal Securities Laws with respect to Acadian Asset Management LLC, BrightSphere Investment Group Inc. and/or their respective subsidiaries and affiliated entities. The recipient of these materials agrees that it will not use any confidential information that may be contained herein to execute or recommend transactions in securities. The recipient further acknowledges that it is aware that United States Federal and State securities laws prohibit any person or entity who has material, non-public information about a publicly-traded company from purchasing or selling securities of such company, or from communicating such information to any other person or entity under circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that such person or entity is likely to sell or purchase such securities.

Acadian provides this material as a general overview of the firm, our processes and our investment capabilities. It has been provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe or to purchase, shares, units or other interests in investments that may be referred to herein and must not be construed as investment or financial product advice. Acadian has not considered any reader's financial situation, objective or needs in providing the relevant information.

The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your original investment. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance or returns. Acadian has taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this material is accurate at the time of its distribution, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of such information.

This material contains privileged and confidential information and is intended only for the recipient/s. Any distribution, reproduction or other use of this presentation by recipients is strictly prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient and this presentation has been sent or passed on to you in error, please contact us immediately. Confidentiality and privilege are not lost by this presentation having been sent or passed on to you in error.

Acadian’s quantitative investment process is supported by extensive proprietary computer code. Acadian’s researchers, software developers, and IT teams follow a structured design, development, testing, change control, and review processes during the development of its systems and the implementation within our investment process. These controls and their effectiveness are subject to regular internal reviews, at least annual independent review by our SOC1 auditor. However, despite these extensive controls it is possible that errors may occur in coding and within the investment process, as is the case with any complex software or data-driven model, and no guarantee or warranty can be provided that any quantitative investment model is completely free of errors. Any such errors could have a negative impact on investment results. We have in place control systems and processes which are intended to identify in a timely manner any such errors which would have a material impact on the investment process.

Acadian Asset Management LLC has wholly owned affiliates located in London, Singapore, and Sydney. Pursuant to the terms of service level agreements with each affiliate, employees of Acadian Asset Management LLC may provide certain services on behalf of each affiliate and employees of each affiliate may provide certain administrative services, including marketing and client service, on behalf of Acadian Asset Management LLC.

Acadian Asset Management LLC is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training.

Acadian Asset Management (Singapore) Pte Ltd, (Registration Number: 199902125D) is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 41 114 200 127) is the holder of Australian financial services license number 291872 ("AFSL"). It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Under the terms of its AFSL, Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited is limited to providing the financial services under its license to wholesale clients only. This marketing material is not to be provided to retail clients.

Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority ('the FCA') and is a limited liability company incorporated in England and Wales with company number 05644066. Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited will only make this material available to Professional Clients and Eligible Counterparties as defined by the FCA under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or to Qualified Investors in Switzerland as defined in the Collective Investment Schemes Act, as applicable.