Concentrated Equity: Standing Out but Not Outstanding

Key Takeaways

- Concentrated equity strategies, i.e., discretionary portfolios that hold a very small number of stocks, have gone mainstream in recent years.

- While the concept has some intuitive appeal, it preys on the behavioral vulnerabilities of asset owners.

- Moreover, in a novel study of institutional equity investments, we find no evidence that concentrated equity strategies outperform. We also highlight special challenges that they pose for asset owners who mistake them for an easy path to “high conviction.”

Table of contents

Investment managers have great incentive to stand out from their peers—or more precisely—to have stood out from their peers. Institutional asset owners hire managers who have produced large positive excess returns.1 Searches are kicked off by scanning databases for strategies that have delivered top-quartile performance. Managers that have outperformed receive fawning attention in the media, both social and traditional.

This focus on demonstrated performance is natural and has some benefits. It fuels managers’ relentless search to discover mispriced assets, which, in turn, is what produces (reasonably) efficient markets. But in a world where distinguishing investment skill from luck is no easy task, hindsight bias has fostered the disturbing normalization of an investing approach that leans into noise—highly concentrated equity strategies.

Preying on Investors’ Behavioral Biases

Concentrated equity strategies, i.e., discretionary strategies that hold a small number of stocks, have been gradually gaining acceptance among institutional asset owners for over a decade. To be sure, there is a substantive aspect to their appeal. The premise of investing with stock pickers who focus on a limited set of “high conviction” holdings tempts many asset owners who are hungry for active returns and wary of paying material fees for “closet passive” products.

The approach also has indirect support from academic literature showing that mutual fund managers’ largest active positions outperform; their other holdings seem dead weight.

But concentrated investing also preys on investors’ tendency to chase performance. Relative to their better-diversified counterparts, concentrated strategies generate noisier returns, i.e., higher active risk. This noise induces greater dispersion in their performance, which means that, whether or not they have superior skill, concentrated managers are likely to be overrepresented among outperformers and, therefore, more likely to attract the eye of performance-hungry asset owners.

What Does the Evidence Show?

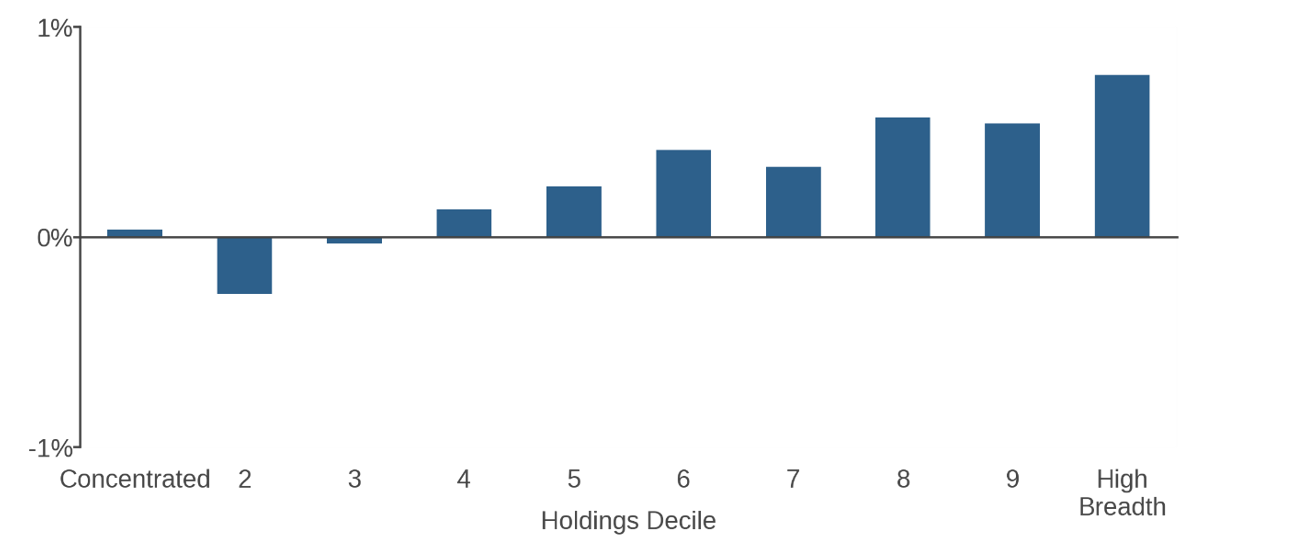

Do concentrated managers actually exhibit greater skill? My colleague, Anshuman Ramachandran and I, studied this question in recent research.2 In an analysis of almost 3,000 institutional long-only U.S. equity strategies over the past decade, we found no evidence that highly concentrated strategies, i.e., strategies in the smallest decile by number of stocks held (median of ~25), outperform their benchmarks to a greater degree than better-diversified ones (Figure 1). We also found no evidence that concentrated managers exhibit superior stock-selection ability. These results held up after controlling for investment style, AUM, and other considerations.

Figure 1: Average Annualized Active Returns by Holdings Decile

Versus manager’s preferred benchmark; based on data from 2013-2023

While greater skill wasn’t evident, the impact of greater noise was. Concentrated managers exhibited larger active drawdowns and were overrepresented in the poorest performance decile (not just the best).

Many asset owners who invest in concentrated strategies understand that any single such portfolio will generate noisy returns. Instead of holding one concentrated strategy, they hold a portfolio of a few. The value proposition is that the asset owner will be better off assuming the tasks of portfolio construction and management while focusing their active managers exclusively on selecting stocks. The hope is that the portfolio of concentrated strategies will have higher risk-adjusted performance than a single diversified strategy.

But this approach reflects two assumptions: not only that concentrated managers possess and (predictably) manifest greater skill than those that are better diversified, but also that asset owners can identify and craft well-risk-managed portfolios of them. The performance analysis in our study disputes the first assumption. Our research also exposed reasons to doubt the validity of the second.

Specifically, we document that concentrated strategies exhibit noisier risk exposures, greater style drift, and suboptimal tradeoffs in systematic alpha drivers. This is hardly surprising in a class of strategies typified by rudimentary portfolio construction methods. Even well-known risk and alpha factor exposures are likely to go unmeasured and unmanaged. That’s simply not the focus of managers who view their task in terms of becoming the next Warren Buffett—trying to identify promising individual companies.

But this also means that the behavior of concentrated strategies is more difficult for asset managers to predict. Ex post, their return streams may stray far from what was expected ex ante. Unfortunately, it is the asset owner who assumes the associated challenges in manager selection, risk management, and performance analysis. These tasks are easier said than done, yet they are routinely waved away in literature promoting concentration.

Too Easy to Imitate

The concept of concentration has a seemingly persuasive logic: In the context of an old-school, labor-intensive stock picking approach, a discretionary PM surely would struggle to form opinions about more than a limited set of companies and to manage an expansive portfolio. Holding a diversified portfolio would imply investing in companies that the manager knows little about, perhaps just to soak up AUM.3

So where does the premise go wrong? As discussed, one reason is hindsight bias. In an investing world filled with noise, it is difficult to discern skill. Strategies, investment approaches, and even asset classes that have performed well attract attention and flows. Concentrated portfolios, in effect, exploit the difficulty that investors have in processing that noise.

In this regard, the recent investing climate has been especially conducive to concentration. In an environment where market rallies have been identified with just a few high-profile stocks (think Magnificent 7), and even benchmarks came to be described as highly concentrated (whether accurately or not4), the notion of limiting investments to a small and stylistically narrow set of names became natural.

But another problem with concentrated investing, which is inextricably tied into its underlying intuition, is that it’s easy. Forming a small, low-turnover portfolio of relatively liquid stocks does not have to be any challenge. For all the good that Warren Buffett has done, he has also created a legion of imitators whose primary occupation seems to be penning folksy investor letters that explain the idiosyncratic genius of their winners, why their losers were the product of circumstances beyond their control, and how they fill their time. While plenty of these wannabes are eventually exposed, many draw substantial assets first.

Conclusion

Are there stock pickers with special skill? Yes. But asset owners would be wise to expect that they are harder than ever to find. Concentrated investing is highly susceptible to copycat approaches. As my colleague Owen Lamont has pointed out, to the extent that the number of holdings in a portfolio has become identified with investment conviction, a misguided and harmful conflation, the metric has also lost all value.5 Individual PMs and product purveyors can too easily take a flyer on launching a “high conviction” strategy to capitalize on the concentration trend.

In summary, it’s time to dismiss the number of holdings as a measure of conviction and to recognize that concentrated equity strategies are a risky and deceptively simple solution for asset owners in pursuit of exceptional skill.

Endnotes

- Goyal, Amit and Sunil Wahal, “The Selection and Termination of Investment Management Firms by Plan Sponsors.” The Journal of Finance 63, issue 4 (August 2008): 1805-1847.

- See Concentrated Equity: Practice versus Premise, Acadian, October 2024

- This logic does not apply to systematic investing approaches. See Concentration, Conviction, and Quant, Acadian, 2015.

- See Owenomics: Magnificent Ignorance about the Magnificent Seven, June 2024.

- See Owenomics: Goodhart’s Law of Active Management, September 2024.

Legal Disclaimer

These materials provided herein may contain material, non-public information within the meaning of the United States Federal Securities Laws with respect to Acadian Asset Management LLC, Acadian Asset Management Inc. and/or their respective subsidiaries and affiliated entities. The recipient of these materials agrees that it will not use any confidential information that may be contained herein to execute or recommend transactions in securities. The recipient further acknowledges that it is aware that United States Federal and State securities laws prohibit any person or entity who has material, non-public information about a publicly-traded company from purchasing or selling securities of such company, or from communicating such information to any other person or entity under circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that such person or entity is likely to sell or purchase such securities.

Acadian provides this material as a general overview of the firm, our processes and our investment capabilities. It has been provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe or to purchase, shares, units or other interests in investments that may be referred to herein and must not be construed as investment or financial product advice. Acadian has not considered any reader's financial situation, objective or needs in providing the relevant information.

The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your original investment. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance or returns. Acadian has taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this material is accurate at the time of its distribution, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of such information.

This material contains privileged and confidential information and is intended only for the recipient/s. Any distribution, reproduction or other use of this presentation by recipients is strictly prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient and this presentation has been sent or passed on to you in error, please contact us immediately. Confidentiality and privilege are not lost by this presentation having been sent or passed on to you in error.

Acadian’s quantitative investment process is supported by extensive proprietary computer code. Acadian’s researchers, software developers, and IT teams follow a structured design, development, testing, change control, and review processes during the development of its systems and the implementation within our investment process. These controls and their effectiveness are subject to regular internal reviews, at least annual independent review by our SOC1 auditor. However, despite these extensive controls it is possible that errors may occur in coding and within the investment process, as is the case with any complex software or data-driven model, and no guarantee or warranty can be provided that any quantitative investment model is completely free of errors. Any such errors could have a negative impact on investment results. We have in place control systems and processes which are intended to identify in a timely manner any such errors which would have a material impact on the investment process.

Acadian Asset Management LLC has wholly owned affiliates located in London, Singapore, and Sydney. Pursuant to the terms of service level agreements with each affiliate, employees of Acadian Asset Management LLC may provide certain services on behalf of each affiliate and employees of each affiliate may provide certain administrative services, including marketing and client service, on behalf of Acadian Asset Management LLC.

Acadian Asset Management LLC is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training.

Acadian Asset Management (Singapore) Pte Ltd, (Registration Number: 199902125D) is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 41 114 200 127) is the holder of Australian financial services license number 291872 ("AFSL"). It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Under the terms of its AFSL, Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited is limited to providing the financial services under its license to wholesale clients only. This marketing material is not to be provided to retail clients.

Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority ('the FCA') and is a limited liability company incorporated in England and Wales with company number 05644066. Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited will only make this material available to Professional Clients and Eligible Counterparties as defined by the FCA under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or to Qualified Investors in Switzerland as defined in the Collective Investment Schemes Act, as applicable.

Don't miss the next Acadian Insight

Get our latest thought leadership delivered to your inbox